- Home

- James McBride

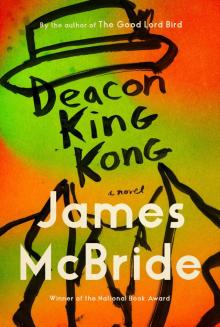

Deacon King Kong Page 4

Deacon King Kong Read online

Page 4

“You ain’t answered me. I trained you to God’s way, son. I taught you Sunday school. I teached you the game.”

Deems’s smile disappeared. The warm glow in his brown eyes vanished; a dark, vacant look replaced it. He was not in a mood for the old man’s bullshit. His long, dark fingers clasping the hero tightened down on it tensely, squeezing out the white mayonnaise and tomato juice, which ran into his hands. “Git gone, Sportcoat,” he said. He licked his fingers, bit into the sandwich again, and whispered a joke to a boy seated on the bench next to him, which sent the two of them chortling.

At that moment, Sportcoat stepped back and calmly reached into his pocket.

Jet, four steps away, still crouched, his hands on his shoelaces, saw the move and uttered the words that would ultimately save Deems’s life. He howled out, “He’s got a burner!”

Clemens, with a mouthful of tuna sandwich, instinctively turned his head in the direction of Jet’s shout.

At that moment, Sportcoat fired.

The blast, aimed at Deems’s forehead, missed, and the bullet struck his ear instead, severing it, the spent bullet clanging off the pavement behind him. But the force of the blast felt like it took Deems’s head off. It tossed him backward over the bench and threw the bite of tuna sandwich against the back of his throat and down his windpipe, choking him.

He landed on his back on the concrete, coughed a few times, then rolled onto his stomach and began choking, desperately trying to rise to his hands and knees as the stunned boys around him scattered and the plaza collapsed into chaos, flyers dropping to the ground, mothers pushing baby carriages at a sprint, a man in a wheelchair spinning past, people running with shopping carts and dropping their grocery bags in panic, a mob of pedestrians fleeing in terror through the fluttering flyers that seemed to be everywhere.

Sportcoat squared his old pistol on Deems again, but when he saw Deems on his hands and knees choking, he had a change of heart. He was suddenly confused. He had dreamed of Hettie the night before wearing her red wig hollering at him about the cheese, and now he was standing over Deems, the dang thing in his hand had fired somehow, and Deems was on the ground in front of him, trying to breathe. Watching him, Sportcoat had an epiphany.

No man, Sportcoat thought, should die on his hands and knees.

As quick as he could, the old man climbed over the bench, mounted Deems, who was on all fours, and with the gun still in one fist, did the Heimlich maneuver on him. “I learnt this from a young pup in South Carolina,” he grunted proudly. “A white fella. He growed up to be a doctor.”

The overall effect, seen from across the square, the nearby street, and every window that faced the plaza, 350 in all, was not good. From a distance, it looked like the vicious drug lord Deems Clemens was on all fours being humped like a dog from the back by an old man, Sportcoat of all people, jouncing atop Deems in his old sports jacket and porkpie hat.

“He fucked him hard,” Miss Izi said later, when describing the incident to the fascinated members of the Puerto Rican Statehood Society of the Cause Houses. The society was only two other people, Eleanora Soto and Angela Negron, but they enjoyed the story immensely, especially the part about Deems’s spitting up the leftover sandwich, which looked, Miss Izi said, like the two tiny white testicles of her ex-husband, Joaquin, after she poured warm olive oil on them when she found him snoring in the arms of her cousin Emelia, who was visiting from Aguadilla.

The humping didn’t last long. Deems had lookouts everywhere, including from the rooftops of four buildings that looked down on the plaza, and they scrambled into action. The lookouts from the roofs of Buildings 9 and 34 bolted for the stairs, while two of Deems’s dope slingers who had scurried away after the initial blast got their wits back and stepped toward Sportcoat. Even though he was still drunk, Sportcoat saw them coming. He released Deems and quickly swung the big barrel of the .38 toward them. The two boys fled again, this time for good, disappearing into the basement of nearby Building 34.

Sportcoat watched them run, suddenly confused again. With the gun still in his hand, he turned toward Jet, who was ten feet off, standing erect and frozen now, one hand on his broom.

Jet, terrified, stared at the old man, who squinted back at him in the afternoon sun, which had come up high now. Their eyes locked, and at that moment Jet felt as if he were looking into the ocean. The old man’s gaze was deep-set, detached, calm, and Jet suddenly felt as if he were floating in a spot of placid sea while giant waves roiled and swelled and lifted up the waters all around him. He had a sudden revelation. We’re the same, Jet thought. We’re trapped.

“I got the cheese,” the old deacon said calmly as the moans of Deems wafted behind him. “Unnerstand? I got the cheese.”

“You got the cheese,” Jet said.

But the old man didn’t hear. He had already turned on his heel, pocketed the gun, and limped quickly toward his building a hundred yards off. But instead of heading to the entrance, he veered off, teetering down the side ramp that led to the basement boiler room.

Jet, frozen with fear, watched him go, then out of the corner of his eye he saw the lights of a police cruiser fly by the street edge of the pedestrian plaza, a distance of about a city block. The car skidded to a stop, backed up, then plunged straight down the pedestrian walkway toward him. Relief washed over him as the squad car fought its way through the fleeing pedestrians, causing the driver to brake, swivel left, then right to avoid the panicked bystanders. Behind that car, Jet saw two more cruisers swing onto the walkway and follow. His relief was so enormous he felt like he’d just taken a great relieving piss, one that had drained him of every bit of life force.

He turned one last time to see the old man’s head disappearing down the basement ramp of Building 9, then felt his guts unlock and found himself able to act. He dropped his broom and leaped over the bench toward Clemens, just as he heard the tires of a squad car slide to a stop behind him. As he crouched over Clemens he heard an officer shouting at him to freeze, stand up, and put up his hands.

As Jet did, he said to himself, I’m no longer doing this. I am finished.

“Don’t move! Don’t turn around!”

Two hands grabbed him from behind and pinned his arms. His face was slammed against the squad car hood. He felt cuffs slapped onto his wrists. From his view, with his ear flush against the hot hood of the car, he could see the plaza, busy as a train station minutes before, completely deserted, a few flyers fluttering in the wind, and the thick, white hand of the cop on the car hood near his face. The cop had put his hand there to brace his weight on it, while the other hand pinned Jet’s head into place. Jet stared at the hand a foot from his eyeballs and noticed a wedding ring on it. I know that hand, he thought.

When his head was snatched from the hood, Jet found himself staring at his old partner Potts. Deems was on the ground, twenty feet off and surrounded by cops.

“I didn’t do nothing,” Jet shouted, loud enough for Clemens and anyone nearby to hear.

Potts spun him around, then patted him down, carefully avoiding the .38 strapped to his ankle. As he did, Jet muttered, “Arrest me, Potts. For God’s sake.”

Potts grabbed him by the collar and swung him toward the backseat of his squad car.

“You’re an idiot,” he murmured softly.

4

RUNNING OFF

Sportcoat walked into the basement furnace room of Building 9 and sat on a foldout chair next to the giant coal furnace in a huff. He heard the wail of a siren, then forgot all about it. He didn’t care about any siren. He was looking for something. His eyes scanned the floor, then stopped as he suddenly remembered he was supposed to memorize a Bible verse for his upcoming Friends and Family Day sermon. It was about righting wrongs. Was it the book of Romans or Micah? He couldn’t recall. Then his mind slid to the same old nagging problem: Hettie and the Christmas Club money.

“We go

t along all right till you decided to fool with that damn Christmas Club,” he snorted.

He looked around the basement for Hettie. She didn’t appear.

“You hear me?”

Nothing.

“Well, that’s all right too,” he snapped. “The church ain’t holding no notes on me about that missing money. It’s you who got to live with it, not me.”

He stood and began to search for a bottle of emergency King Kong that Sausage always kept hidden someplace, but was still pie-eyed and feeling addled and murky. He pushed around the discarded tools and bicycle parts on the floor with his foot, muttering. “Some people got to stay mad to keep from getting mad,” he grumbled. “Some goes from preaching to meddlin’ and meddlin’ to preaching and can’t hardly tell the difference. Well, it ain’t my money, Hettie. It’s the church’s money.” He stopped moving items with his foot for a moment and stilled, talking to the air. “It’s all the same,” he announced. “You got to have a principle or you ain’t nothing. What you think of that?”

Silence.

“I thought so.”

Calmer now, he started searching again, bending down and talking as he checked toolboxes and under bricks. “You never did think of my money, did you? Like with that old mule I had down home,” he said. “The one old Mr. Tullus wanted to buy. He offered me a hundred dollars for her. I said, ‘Mr. Tullus, it’ll take a smooth two hundred to move her.’ Old man wouldn’t pay that much, remember? That mule up and died two weeks later. I coulda sold her. You shoulda told me to turn her loose.”

Silence.

“Well, Hettie, if I weren’t taking that white man’s good hundred dollars on principle, I surely ain’t gonna take no mess from you ’bout some fourteen dollars and nine pennies you done squirreled up in Christmas Club money and hid someplace.”

He paused, looked out the corner of his eye, then said softly, “It is fourteen dollars, ain’t it? It ain’t, say, two or three hundred dollars, is it? I can’t do three hundred dollars. Fourteen is sheep money. I can raise that sleeping. But three hundred, that’s over my head, honey.”

He stopped moving, frustrated, still looking around, unable to find what he was looking for. “That money . . . it ain’t mine, Hettie!”

There was still no answer, and he sat down again in the folding chair, flummoxed.

Sitting in the cold seat, he had an unfamiliar, odd, nagging feeling that something terrible had occurred. The feeling wasn’t unusual for him, especially since Hettie died. Normally he ignored it, but this time it felt bigger than usual. He couldn’t place it, then suddenly spied the prize he was looking for and forgot about the problem instantly. He stood up, shuffled over to a hot-water heater, reached under it, and pulled out the bottle of Rufus’s homemade King Kong.

He held the bottle up to the bare ceiling lightbulb. “I say a drink, I say a glass. I say do you know me? I say the note is due! I say bring the hens! I say a poke and a choke, Hettie. I say God only knows when! Brace!”

Sportcoat turned up the bottle, drank a deep swallow, and the nagging feeling bubbled away. He placed the bottle back in its hiding place and relaxed in his seat, satisfied. “G’wan, King Kong,” he murmured. Then he wondered aloud, “What day is this, Hettie?”

He realized she wasn’t speaking to him, so he said, “Hell, I don’t need ya. I can read . . . ,” which was actually not true. He could read a calendar. Words were another matter.

He rose, ambled over to a weathered wall calendar, peered at it through the haze of his drunken glow, then nodded. It was Thursday. Itkin’s day. He had four jobs, one for every day but Sunday: Mondays he cleaned Five Ends church. Tuesdays he emptied the garbage at the nursing home. Wednesdays he helped an old white lady with the garden of her brownstone. Thursdays he unloaded crates at Itkin’s liquor store, just four blocks from the Cause Houses. Fridays and Saturdays had once been baseball practice for the Cause Houses baseball team before it disbanded.

Sportcoat looked over at the wall clock. Almost one o’clock. He had to get to work.

“Gotta go, Hettie!” he said cheerily.

He pulled out the bottle again and took another quick nip of the Kong, slid it back to its hiding place, and walked out the back door of the basement, which exited a block away from the plaza flagpole. The street was clear and quiet. He wobbled easily, freely, the fresh air steadying him a bit and partially lifting the drunken haze. Within moments he was heading down the row of neat shops that lined Piselli Street and the nearby Italian neighborhood. He loved walking to Mr. Itkin’s place, toward downtown Brooklyn, seeing the neat row homes and storefronts, the stores full of shopkeepers, some of whom waved at him as he walked past. Stacking booze and helping customers cart their wine to their cars was one of his favorite small jobs. Small jobs that didn’t last more than a day and didn’t require tools were perfect for him.

Ten minutes later, he ambled to a door under an awning that read Itkin’s Liquors. As he reached it, a police car roared past. Then another. He paused at the door, hastily felt in his jacket vest pocket, where he stored booze or any empty or stray liquor bottles that might’ve been stuffed in there from some previous unremembered moment of elbow bending—forgetting his hip pockets altogether—then turned the door handle.

The doorbell tingled as he entered and closed it behind him, shutting off the howl of yet another police car and ambulance roaring past.

Mr. Itkin, the owner, a stout, easygoing Jew, was wiping the countertop, his paunch protruding over the edge. The store was silent. The air-conditioning was blasting. It was still five minutes till opening time. Itkin nodded over Sportcoat’s shoulder at the cop cars racing toward the Cause Houses. “What’s going on out there?”

“Diabetes,” Sportcoat said, plodding past Itkin’s counter to the back stockroom, “killing ’em off one by one.” He slipped into the back room, where stacks of newly arrived liquor boxes awaited opening. He sat down on a crate with a sigh. He didn’t care about any sirens.

He removed his hat and wiped his brow. The counter where Itkin stood was a good twenty feet from the door to the back room, but Itkin, from his vantage point at the edge of the counter, could see Sportcoat clearly. He stopped wiping and called out, “You look a little peaked, Deacon.”

Sportcoat dismissed the concern with a grin and an easy yawn, stretching his arms wide. “I’m feeling dandy and handy,” he said. Itkin returned to wiping his counter, moving out of sight to work the other side of it, while Sportcoat, carefully keeping out of Itkin’s sightline, grabbed a root beer from a crate, cracked it open, took a long drink of it, put it down on a nearby shelf, and began stacking boxes. He glanced to make sure Itkin was still at the far end of the counter and out of view, then, with the practiced smoothness of a cat burglar, he snatched a bottle of gin out of a nearby case, unscrewed its cap and poured half its contents into the root beer can, closed the bottle, stuffed it into his jacket hip pocket, removed the jacket, and placed it on a nearby shelf. The coat landed with an odd clank. For a moment Sportcoat thought he had a forgotten bottle stuffed in the pocket on the other side, since he’d only quickly rifled through his chest pockets before entering the store and not his hip pockets, so he snatched up the coat again, fished in the hip pockets, and yanked out the old .38.

“How’d my army gun get here?” he muttered.

Just then the jingle of the door sounded. He shoved the gun back into the jacket and glanced up to see several of the day’s first customers entering, all of them white, followed by the familiar porkpie hat and brown worried face of Hot Sausage, still wearing his blue Housing Authority janitor uniform.

Sausage lingered at the door a moment, feigning interest in a nearby liquor display as the paying customers fanned out. Itkin, irritated, glanced at him.

Sausage blurted, “Deacon left something at home.”

Itkin nodded curtly toward the back room, where Sportcoat could be see

n, then was called down an aisle by one of the customers, which allowed Sausage to slip past the counter and into the back room. Sportcoat noticed he was sweating and breathing hard.

“Sausage, what you want?” he said. “Itkin don’t like you back here.”

Hot Sausage glanced over his shoulder, then hissed, “Goddamn fool!”

“What you so hot about?”

“You got to run! Now!”

“What you fussing at me for?” Sportcoat said. He offered the root beer can. “Have a sip-sot for your coal-top.”

Sausage snatched the root beer soda can, sniffed it, then slammed it down on a crate so hard liquid popped out the opening.

“Nigger, you ain’t got time to set around sipping essence. You gotta put your foot in the road!”

“What?”

“You got to go!”

“Go where? I just got here.”

“Go anyplace, fool. Run off!”

“I ain’t leaving my job, Sausage!”

“Clemens ain’t dead,” Sausage said.

“Who?” Sportcoat asked.

“Deems! He ain’t dead.”

“Who?”

Hot Sausage stepped back, blinking.

“What’s the matter with you, Sport?”

Sportcoat sat down on a crate, wearily, shaking his head. “Don’t know, Sausage. I been talking to Hettie ’bout my sermon for Friends and Family Day. She got to hollering about that cheese again, and the Christmas Club money. Then she throwed in my momma. She said my momma didn’t—”

“Cut that mumbo jumbo, Sport. You in trouble!”

“With Hettie? What I done now?”

“Hettie’s been dead two years, fool!”

Sportcoat puckered his face and said softly, “You ain’t got to speak left-handed about my dear Hettie, Sausage. She never done you no wrong.”

“She wasn’t so dear last week, when you was bellowing like a calf about that Christmas Club money. Forget her a minute, Sport. Deems ain’t dead!”

Miracle at St. Anna

Miracle at St. Anna The Good Lord Bird

The Good Lord Bird Song Yet Sung

Song Yet Sung The Color of Water

The Color of Water Kill 'Em and Leave

Kill 'Em and Leave Deacon King Kong

Deacon King Kong Miracle at St. Anna (Movie Tie-in)

Miracle at St. Anna (Movie Tie-in)