- Home

- James McBride

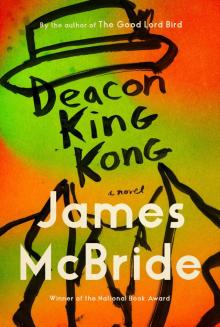

Deacon King Kong Page 6

Deacon King Kong Read online

Page 6

“Naw. Bad for my throat. I’m a singer.”

“What kind of singing?”

“The best kind,” the old man said gaily.

Elefante stifled a smile. He couldn’t help himself. The old bugger barely seemed capable of drawing air. “Sing me a song then,” he said. He said it for amusement, and was surprised when the old man moved his head from side to side to stretch his neck muscles, cleared his throat, stood up, thrust his whiskered chin toward the ceiling, spread his thin arms, and burst into a gorgeous, clear tenor that filled the room with glorious, lilting song:

I remember the day, ’twas wild and drear

And night to the Hudson waves.

Our parson bore a corpse on a bier

To lie in the convict’s grave.

Venus lay covered and taut

She was the beauty of Willendorf

She rests at the bottom of a shallow grav—

He broke off in a fit of coughing. “Okay, okay,” Elefante said, before he could continue. Two of the Elephant’s men who were trooping in a steady line hauling crates back and forth through the boxcar to a waiting box truck paused to smile.

“I ain’t finished yet,” the old man said.

“That’s good enough,” Elefante said. “Don’t you know any Italian songs? Like a trallalero?”

“If I said I knew what that was, I’d be codding ya.”

“It’s a song from northern Italy. Only men sing it.”

“Get your own bulldogs to sing that one, mister. I got something better,” the Irishman said. He coughed again, a racking one this time, then regained himself and cleared his throat. “I take it you’re in need of money?”

“I look that bad?”

“I have a small shipment that needs to go to Kennedy airport,” he said.

Elefante glanced at the two men, who had stalled to watch. They quickly scurried back to work. This was business. Elefante motioned for the Irishman to sit in the chair next to his desk, out of the way of foot traffic.

“I don’t haul stuff to the airport,” Elefante said. “I do storage and light hauling. Mostly for grocery stores.”

“Save that for the government,” the Irishman said. “Salvy Doyle told me you could be trusted.”

Elefante was silent for a moment, then said, “Salvy, last I heard, was pushing up worms in Staten Island someplace.”

The Irishman chuckled. “Not when he knew me. Or your father. We were friends.”

“My father didn’t have friends.”

“Back when we was guests of the state your father had many friends, may God bless him in his eternal resting place.”

“If you want a wailing wall, use the desktop,” Elefante said. “Get the show on the road.”

“What?”

“What’s your point, mister?” Elefante said impatiently. “What do you want?”

“I already said it. I need something moved to Kennedy.”

“And past Kennedy?”

“That’s my business.”

“Is it a big shipment?”

“No. But it needs a trusted ride.”

“Get a cab.”

“Don’t trust a cab. I trusted Salvy—who said you could be trusted.”

“How did Salvy hear of me?”

“He knew your father. I told you.”

“Nobody knew my father. He was hard to know.”

The Irishman chuckled. “You’re right. I don’t think he said more than three words a day.”

That was true. Elefante filed the fact that the Irishman knew this away for posterity. “So who do you work for?” he asked.

“Myself,” the Irishman said.

“What’s that mean?”

“It means I don’t need a doctor’s note when I call in sick,” the Irishman said.

Elefante snorted and stood up. “I’ll have one of my guys run you to the subway. It’s dangerous around here at night. The junkies in the Cause will stick a pistol in your face for a quarter.”

“Wait, friend,” the old man said.

“I’ve known you two minutes and I’m tired of the friendship already, mister.”

“The name’s Driscoll Sturgess. I run a bagel shop in the Bronx.”

“You oughta run a lying service. An Irishman running a bagel shop?”

“It’s legal.”

“You better head back to whatever packing crate you call home, mister. My pop had no Irish friends. The only Irish my father talked to were cops. And they were like a fungus. You want a ride to the subway or not?”

The old man’s cheeriness emptied out of his face. “Guido Elefante knew plenty Irish in Sing Sing, sir. Lenny Belton, Peter Seamus, Salvy, myself. We were all friends. Gimme a minute, will ya?”

“I ain’t got a minute,” the Elephant said. He stood and moved to the doorway, expecting the old man to rise. Instead, Driscoll peered up at him and said, “You got a good company here. How’s the health of it?”

Elefante snapped his glance down to the Irishman.

“Say that again,” he said.

“How’s the health of your trucking company?”

Elefante sat back down and frowned. “What’s your name now?”

“Sturgess. Driscoll Sturgess.”

“You got any other names?”

“Well . . . your father knew me as the Governor. And may your health always be fine, and the wind at your back. May the road rise up to meet you. And may God hold you in the palm of His hand. That’s a poem, lad. I made up a ditty with the last line of it. Wanna hear it?” He stood up to sing, but Elefante reached a long arm out, grabbed the old man’s jacket, and tugged him back into his chair.

“Sit a minute.”

Elefante stared at him a long moment, feeling like his ears had just blown off his head, his mind buzzing the red alarm of an important, hazy memory. The Governor. He’d heard the name before, in a long-distant past. His father had mentioned it several times. But when? It had been years ago. It was near the end of his father’s life, and he, Elefante, was nineteen then, at an age when teenagers didn’t listen. The Governor? The governor of what? He dug deep in the recesses of his mind, trying to draw it out. The Governor . . . the Governor . . . It was something big . . . it had to do with money. But what?

“The Governor, you say?” Elefante said, stalling.

“That’s right. Your poppa never mentioned me?”

Elefante sat a moment, blinking, and cleared his throat. “Maybe,” he said. His father, Guido Elefante, had had a six-word vocabulary, spoken four times a day, but each word was a saber that cut through the dimly lit bedroom where he’d spent the last years of his life, crippled by a stroke suffered in prison, his grim, harsh commands cutting into the heart of his once happy-go-lucky boy, who had spent most of his growing years running wild with a mother unable to control him, raised by neighbors and cousins, while Guido had spent most of Elefante’s childhood doing time in jail for a crime Guido never disclosed. Elefante was eighteen when his father came out of jail. The two were never close. Guido, felled by another stroke that got him for good just short of his son’s twentieth birthday. By then, the son had spent a good part of his young life without a father. Other than a few occasions when he was five and the old man took him swimming at the Cause Houses pool, Elefante had few memories of leisure time with his pop. The old man who came home from jail that last time was silent as ever, a grim, suspicious, stone-faced Italian, ruling his wife and son with iron efficiency, guided by the one motto that he forced into his son’s consciousness, one that had led Guido safely from the poverty-stricken docks of Genoa to his dying moments in a handsome Cause brownstone bought and paid for, cash: Everything you are, everything you will be in this cruel world, depends on your word. A man who cannot keep his word, Guido said, is worthless. Only in his later years

did Elefante truly appreciate his old man’s power, his ability, even bedridden and debilitated, to manage his trucking, storage, and construction business with clever, assured firmness. The old man with an odd wife, working his business in a world of two-faced mobsters with no imagination, and always willing to break his long silences with the same warnings: Keep a tight mouth. Never ask questions of customers. Remember, we’re just a bunch of poor Genoans working for Sicilians who don’t have our health in mind. That and health. The old man was a fanatic about health. Your health, your health is everything. Keep your health in mind. Elefante heard that so much he grew sick of it. At first Elefante believed that credo came from the old man’s own health misfortunes. But as the old man spiraled toward death, the admonition took on new meaning.

As he sat before the elderly Irishman in his boxcar, the moment of realization suddenly tumbled into Elefante’s consciousness with startling efficiency, landing on his insides with a heaviness that felt like a blacksmith’s hammer falling on an anvil.

They were in the old man’s bedroom just days before he died. The old man had sent his mother to the store, claiming he needed fresh orange juice—something he disliked but occasionally drank for his wife’s sake. They were in the bedroom, just the two of them, watching Bill Beutel, the longtime anchorman on Channel 7, giving the local news, Elefante in the room’s only chair, the old man propped on the bed. His pop seemed distracted. He raised his head from his pillow and said, “Turn the TV sound up.”

Elefante did as he was told, then moved his chair next to the bed. As he tried to sit, the old man reached up and grabbed his shirt and pulled him onto the bed, yanking his son’s head close to his. “Keep your eyes open for someone.”

“Who?”

“An old fella. Irishman. The Governor.”

“The governor of New York?” Elefante asked.

“Not that crook,” his father said. “The other Governor. The Irish one. That’s his name: the Governor. If he shows—and he probably won’t—he’ll ask about your health. That’s how you’ll know it’s him.”

“What about my health?”

His father ignored him. “And he’ll sing about the road rising up to meet you, and the wind being at your back and God being in the palm of your hand. All that Irish Catholic crap. If he’s crowing that and asking about your health, that’s him.”

“What about him?”

“I’m holding something for him, and he’s come to collect it. Give it to him. He’ll treat you fair.”

“What’re you holding?”

But then they heard the door open and his mother return, so the old man shut down, saying they’d talk later. Later never came. The old man slipped into incomprehensibility a day later and died.

Elefante, seated before the Irishman, who was staring at him oddly, tried to keep his voice even. “Poppa did mention something about health. But that was a long time ago. Just before he died. I was twenty, so I don’t remember so well.”

“Ah, but a fair-play mate he was. He never forgot a friend. A better man I never knew. He looked out for me in prison.”

“Look, get your blockers out the backfield, would ya?”

“What?”

“Put the show on the road, mister. What you selling?”

“I’ll say it once again for Mother Mary. I need something moved to Kennedy.”

“Is it too big for a car?”

“No. You can fit it in your hand.”

“You wanna play blackjacks and spout riddles all day? What is it?”

The Governor smiled. “If I was light-headed enough to drag a barrel full of trouble to a friend’s house, what kind of man would I be?”

“That’s touching, but it sounds like a lie.”

“I’d move it myself,” the old Irishman said. “But it’s in storage.”

“Get it out then.”

“That’s just it. I can’t. The header running the storage place don’t know me.”

“Who’s the guy?”

The old man smirked and peered at Elefante out the side of his one good eye. “I’d tell you in installments, but at my age, how’s that gonna work out? Whyn’t you wind yer neck in and pay attention?” He smiled grimly, then from his chair sang softly:

Wars were shared and gay for each

Until the Venus faced the breach

The Venus, the Venus, so dear to me

At Willendorf always her image be.

The Venus oh beauty

Now covered and taut

Lost to me, but not for naught.

When he stopped, he found Elefante glaring at him, his lips pursed. “If you wanna keep your teeth,” Elefante said, “don’t sing no more.”

The old Irishman was nonplussed. “I got no tricks,” he said. “Something fell in my lap many a year ago. I need your help getting it. And moving it.”

“What is it?”

Again the old man ignored the question. “I’m on a short lease, lad. I’m on the way out. It won’t do me no good. My lungs are going. I got a grown lass, a daughter. I’m giving her my bagel business. It’s a good, clean business.”

“What’s an Irishman doing baking bagels?”

“Is that illegal? No worries about the cops, son. Come up and see it if you want. It’s a good operation. We’re in the Bronx. Right off the Bruckner Expressway. You’ll see I’m square.”

“If you’re so square and tidy, give your daughter what you got and live happily ever after.”

“I said I don’t want my daughter mixed up in it. You can have it. You can keep it. Or sell it. Or sell it and give me a little piece if you want, and keep the rest for yourself. However you like. That’ll be the end of it. At least it won’t be wasted.”

“You oughta be a wedding planner, mister. First you want me to move it. Then you want to give it to me. Then you want me to sell it and give you a piece. What is it, for Christ’s sake?”

The old man looked at Elefante sideways. “Your old man told me a story once. He said you wanted a job working for the Five Families when he came out. You wanna know how the story ends?”

“I already know how it ends.”

“No you don’t,” the Governor said. “Your poppa bragged on you in prison. Said you would run his business good someday. Said you could keep a secret.”

“Sure can. Wanna hear one? My poppa’s dead, and he ain’t paying my bills now.”

“What you getting hepped for, son? Your poppa gifted you. He put this thing up. Stored it for me years ago. And you got the key to it.”

“How do you know I didn’t use the key and sell the thing already, whatever it is?” Elefante asked.

“If you’d done that, you wouldn’t be making a bag of it in this blessed boxcar in the wee hours, moving this shit you call goods, which, if I’m remembering right from the old days, let’s see . . . twelve-foot box truck, thirty-four crates, at forty-eight dollars a crate, if it’s cigarettes and maybe a few cases of booze, you’re looking at . . . maybe five thousand gross and fifteen hundred clams in your pocket after everybody’s paid, including Gorvino, who runs these docks—which if your father knew you were still working for him, he’d probably marmalade ya. He’d be shook, that’s for sure.”

Elefante blanched. The old guy had balls. And smarts. And maybe a point. “So you can add figures,” he said. “Where’s this thing that you can’t name?”

“I just named it for you. It’s in a storage box probably.”

Elefante ignored that. He hadn’t heard any name of anything. Instead he asked, “You got a slip?”

“A what?”

“A receipt? A storage slip. Showing the box is yours?”

The Irishman frowned. “Guido Elefante didn’t give receipts. His word was good enough.”

He was silent as Elefante took that in. Finally Elefante spoke.

“I got fifty-nine storage lockers. All padlocked by whoever rents them. Only the owners got the keys.”

The Irishman laughed. “Be a good lad. Maybe it’s not in a storage box.”

“Where is it then? Buried in a lot someplace?”

“If you want to relax with your slippers, I’m not your man. It’s got to be clean, son. Clean as a bar of Palmolive soap. Your poppa would see to it.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Pull your socks up, lad. I just told you. Wherever it is, it’s got to be clean. It might just be a bar of soap, or be in a bar of soap. That’s how small it is. That’ll keep it clean, I suppose, if you put it in a big bar of soap. It’s about that size.”

“Mister, you come in here singing riddles. You say this junk—whatever it is—needs a truck ride to the airport even though it’s the size of a bar of soap. That it’s got to be clean like soap, that it might even be soap. Do I look stupid enough to run around for a bar of soap?”

“You could buy three million dollars’ worth of suds with it. Give or take a few dollars. If it’s in good shape,” the Irishman said.

Elefante watched the worker closest to him lug a crate from the door of the boxcar to the waiting truck outside. He watched him shove the crate into the truck without saying a word or changing his expression, and decided the man hadn’t overheard.

“I’d let you talk pretty to me like that all night if I could,” he said. “But I’d hate myself in the morning. I’ll get one of my guys to take you back to the Bronx. The subway ain’t what it used to be. I’ll do that for my poppa’s sake.”

Sturgess held up an old, wrinkled hand. “I’m not having you on. I got no muscle to move this thing. I know somebody who might want to buy it in Europe. That’s why I want to get it to Kennedy. But now, talking to you, you’re a smart laddie, I think it’s better if you take it. Sell it if you want, give me a small piece if you can. If you don’t, that’s okay. I got nothing except a lass at home. I don’t want no trouble for her. She runs my business good. I just don’t want to waste the thing, is all.”

Miracle at St. Anna

Miracle at St. Anna The Good Lord Bird

The Good Lord Bird Song Yet Sung

Song Yet Sung The Color of Water

The Color of Water Kill 'Em and Leave

Kill 'Em and Leave Deacon King Kong

Deacon King Kong Miracle at St. Anna (Movie Tie-in)

Miracle at St. Anna (Movie Tie-in)